I’ve had my fair share of trouble aboard Panache, but nothing quite as somber as my fractured rudder. The accident left me unable to carry on, literally and figuratively. Looking into a mirror I knew I had seen this before, although I barely recognized it through my bearded face. I had seen it in Costa Rica, when I had the misfortune of watching my friends aboard Bella Star suffer a lightning strike that rendered their Hans Christian void of electronics. The only reasonable play anyone has in a situation like this is to try and move on, to embrace your situation and understand that sometimes the best of times come from the worst. I learned this lesson the way I learn most things as an American, from watching movies. This Hollywood teaching is not an easy one to swallow, but both Aaron and Nicole did so without haste. Within days I watched hopelessness turn to acceptance, and a plan was in motion to get Bella Star back underway. As Hollywood promised, the accident gave all of us an opportunity to do some seriously amazing inland travel.

Looking in the mirror, it was now my turn to swallow the same rationale. The Hollywood special. It’s harder than it sounds, and no matter how hard I tried, I could see no silver lining. Vlad was leaving, and the rudder repair was moving at a snail’s pace, partially because of the intermittent rain Niue needed to break its drought, but mainly because sitting on the internet was an easier reality than being shipwrecked. When Facebooking lost its appeal, I surrendered to looking longingly out the Niue Yacht Club window trying to figure out my next plan of action. Would Vlad and I be able to fix the rudder? Even if we could fix it, would we even be able to put the rudder back on Panache? Where would I go? And the biggest question, would I have enough money once I got there? My bank account was looking bleak, my camera equipment was starting to show signs of fatigue, and I could barely recognize myself in the mirror. New Zealand seemed impossibly far away, which left me with the option of leaving Panache on a “cyclone-proof” mooring somewhere in Vava’u, Tonga or Fiji or hauling the boat out in American Samoa. Or maybe I’d just say “To hell with everything!” and leave Panache right here in Niue. I had options, but I was unsure if I had enough money to execute any of them, minus abandoning Panache. Abandoning Panache? Was I really thinking like this!? I didn’t want to stop cruising, but it was cyclone season and I had to put the boat somewhere. At the beginning of this trip, I told myself I would be more decisive, but there are still moments where I wish I could just have someone tell me what to do. I can see the advert now: Like telling people what to do? Do you lack the emotion apathy? Email me if you’re interested in the position.

Ever since I arrived in the South Pacific, people have been saying the cyclone season is going to be violent this year. They told me in the Marquesas, in Tahiti, in the Cook Islands and now in Niue. “Yeah man, this year is going to be full of crazy strong cyclones. This is a great season for mangos. Mangos only have good years when fierce cyclones are on the horizon. Cyclone Heta was during a good mango year.” Great, if I didn't have enough to worry about. Cyclone Heta was a category 5 cyclone that practically wiped Niue off the face of the earth in late-December/early-January 2004. You can still see some of the damage from the cyclone in palm trees that were blown down 90 degrees and then started growing back towards the sky creating a huge L-shaped kink. The palm trees were constant reminders that Panache was in the wrong place at the wrong time, and if this rain kept persisting, there would be nothing I could do about it.

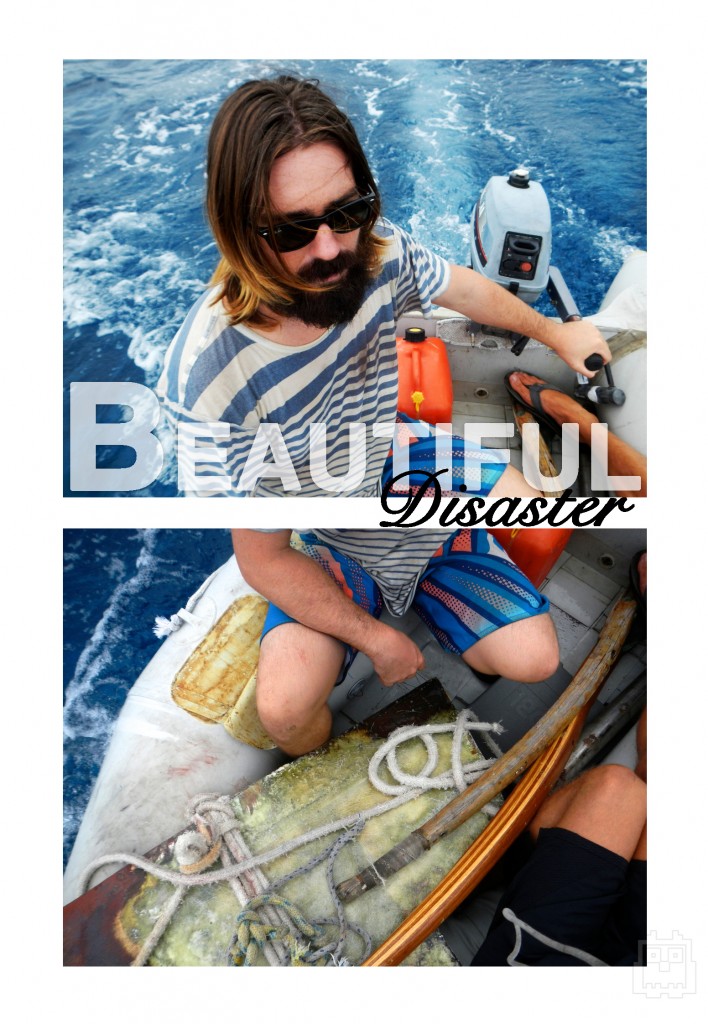

When the rain finally let up, Vlad and I managed to sabotage our own project by accidentally adding more epoxy resin to the epoxy resin instead of the hardening agent. The next morning we had the enjoyment of discovering our filling compound hadn't dried one bit. A day lost, and a big mess to clean up. This was the low point.

Between working on the rudder and waiting for our latest weave of epoxy and fiberglass to dry, we spent lots of time talking with Brian and Ira (the couple who run the NYC), and whomever wandered in. The news of our accident spread quickly as any gossip would on an island that’s home to 1400 people. Everyone was interested to hear our story, and I would joke that the reef hit us, not the other way around. That reef came out of nowhere!

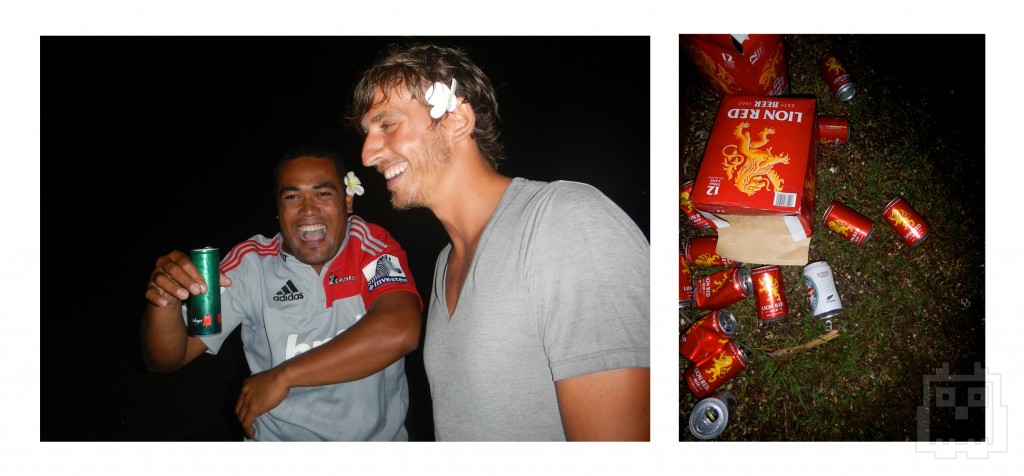

I had crashed my way into a seriously friendly, tight-knit community. This was a pivotal point for my morale, one that truly allowed me to embrace my circumstance. Yep, I am shipwrecked at the moment, but as my uncle Curtis pointed out, I am “Stranded on a beautiful tropical island in the South Pacific,” with friendly people willing to help repair my spirit and my rudder. In Curtis’ words, I may “never get another chance to live this dream again. The future will bring bills, children and commitments ... [my] voyage has only just begun.” Curtis definitely helped me find the bright side to escape my funk, and after one big night out with some locals, my spirit was repaired. The morning was hazy from too many Steinlagers, regardless, we had enough sense to add hardener to our epoxy mix. We were finally starting to repair Panache with a healthy outlook.

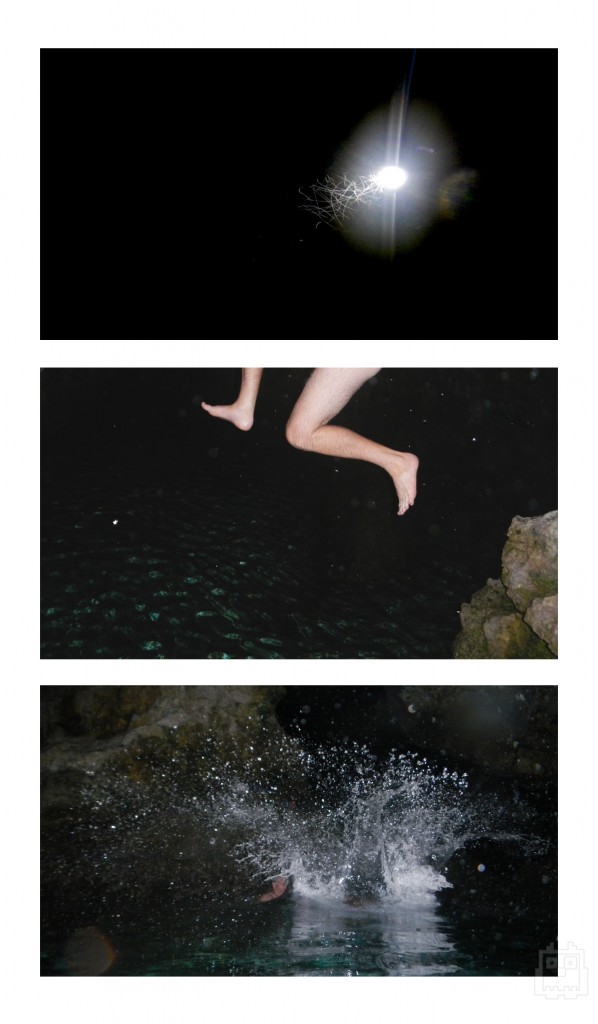

After a night of heavy drinking, the safest thing to do is jump off high rocks into the dark sea at one of the many sea tracks.

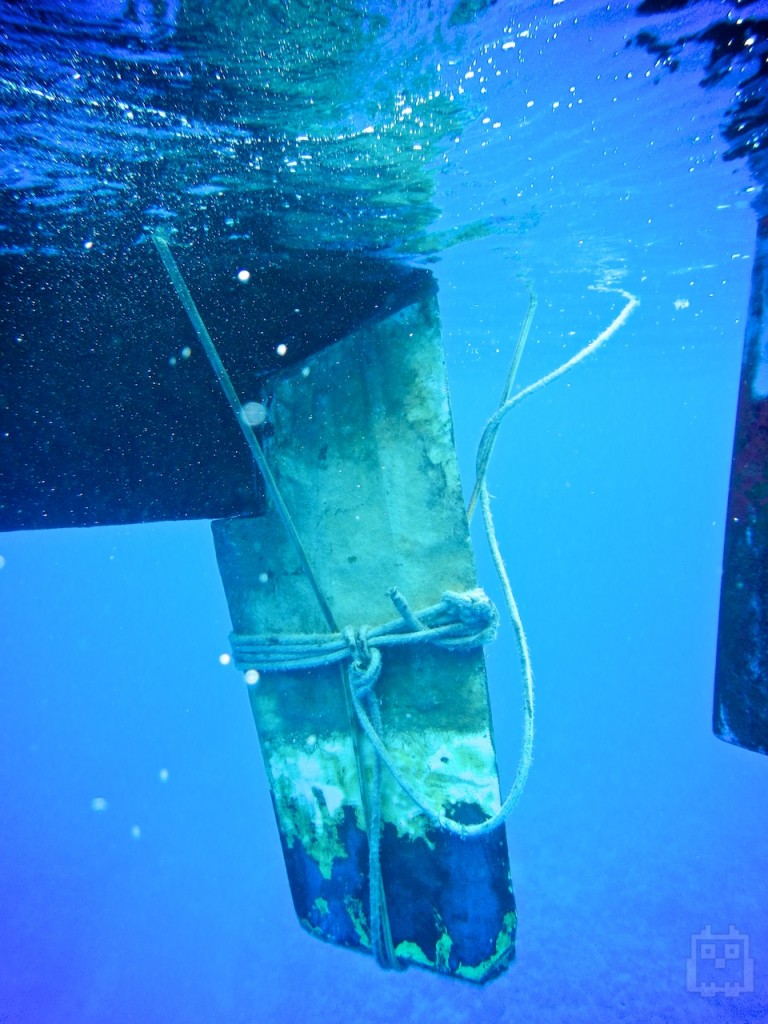

Putting the rudder back on the boat was a bit of an engineering challenge with no room for error. Panache was sitting in 50 feet of water, and if the 100ish pound rudder were to drop to the sea floor, it was unlikely that we would get it back without a diver. Vlad and I lashed a thick line around the rudder and slowly lowered it into the abyss. This was a tense moment. We looped another line into the water and attached it to either side of the boat to act as a saddle for the rudder, allowing us to guide the rudder post into the steering column. Vlad was on deck as a line handler, and I was in the water cowboying the rudder into position. When aligned, Vlad pulled up on both saddle lines and bolted on the tiller. It’s an easy explanation, but the actual job was much more tedious and involved lots of swearing. In the middle of the commotion, Vlad and I got into one of the few arguments we had during all of our time together. The focus of the argument centered on color, specifically what constituted “gold.” You see, we had two lines in the water. The one attached directly to the rudder was cream-colored, and the one attached to the boat (and used as the saddle) was gold. Or so I thought. I asked him to pull in on the gold line, and thus the questions and argument began. All my arguments tend to be laced with stupidity, but this one will go down in history. After coming to a forced understanding of what the color gold looks like, Vlad pulled on the correct line, and Panache’s rudder was repaired – and right on time, because Vlad was flying out the next day.

Our last day on Niue was spent with Mike and Hine, two New Zealanders who manage a noni farm on the SE side of Niue. The noni looks like an oblong baseball that transitions in color from light green to white as it ripens. Oh, and it smells and tastes like blue cheese. Some people call it vomit fruit. I happily tried it, and it does strangely taste exactly like blue cheese (or vomit, depending on how much you like blue cheese). The farm grows the fruit and processes it into a juice that’s sold to the Chinese as a health elixir. The exact health properties of noni are not that exact, but there is no question that they are there. I have heard many applications of the fruit, even as a topical antibiotic. Who knows.

Mike gave me the complete lifecycle of a noni fruit. When mature, a plant can produce about 10 pounds of ripe fruit every month. Harvests are sent through a cleaning machine and then directed through a combine to create a mash. After a large slurry of noni mush is created, it is slung through a massive centrifuge filter and then stored in vats to let the larger particles settle out before the juice is flash pasteurized and bottled. Most of the equipment was purchased second hand from winemakers in New Zealand. The whole process uses a fair amount of water collected from the rain-collecting system that funnels water off the roof and into huge silos. Fun fact: during droughts, huge barn owls in search of water get trapped in these silos and die a watery death. I hear the cleanup is a pain. I poked my head into one of these water tanks, hoping I could save a silly owl, but was strangely disappointed that the tank was owl-free. Looking around, my first thought was, “What a wonderful place to go swimming.” My next thought was, “Wait, how the fuck would I get out of here?” I guess that’s what separates us from the owls.

Brandishing super-human noni strength, we set out to explore some of the freshwater caves hidden deep within Niue’s interior. The first cave was a secret spot Mike stumbled across in an old Niue travel guide from the 70s. A short drive out of Alofi, and we were out of the car and bushwhacking through the spider web laden forest. I felt like I was walking though the opening of an Indiana Jones movie, carefully planting my feet to avoid stepping on some forgotten booby trap. The forest eventually washed against a huge wall of limestone with a deep, scar-like chasm at its base. As we casually descended into the cave, the temperature and sounds of the surface world dampened to an inaudible murmur. We were beyond a screams reach, but all we could do was giggle. Yes, giggle. My whole body and mind was telling me this wasn't possible, but it was, and for some reason this made me laugh like a little girl who just met Justin Bieber. Down and down we went until we saw a crystal-clear blue lagoon, just barely visible by the ambient light slithering into the cavern. The water was cool and fresh. Our torch smeared shards of light throughout the cave and illuminated our surroundings just enough to navigate. The length of the cave was unimpressive, but the depth appeared to be bottomless. I don’t consider myself claustrophobic, but after testing the depth of the cave I couldn't help but feel a shred of confused spatial discomfort. Where were we? Fifteen minutes after entering the cave, Vlad was starting make shadow foot puppets against the cave wall. More giggling and then it was time to move on. We resurfaced to the sticky atmosphere of land dwellers, and the heat and humidity rushed us to our next cave.

Before continuing our subterranean tour, we had to drive through an off-road trail that cuts the Huvalu Forest, an environmentally protected area, in half. Mike explained that the area was dangerous because of how turned around you can get. If that wasn’t enough, the many sinkholes that can literally eat you alive would make even the most veteran bushwhackers pause. On a couple of occasions, tourists have gone missing here for days before reappearing in Alofi looking like an extra from Michael Jackson’s Thriller music video. For an island that’s roughly only 120-square miles, the place packs quite an impressive spectrum of landscapes.

To arrive at our next chasm we had to walk through Uga country. Ugas are coconut crabs also called robber crabs. They look like hermit crabs on steroids, can cut your finger off with their pinchers and love the taste of the rich coconut meat. Pacific islanders conversely love the taste of Uga and actively hunt them for a delicious snack. I have never eaten an Uga, but I am told the meat is strangely sweet. Every coconut we passed had a claw-drilled hole in it, an absent reminder that you are in the Uga’s domain. The landscape was surreal: jagged mounds of raised reef so sharp you could shave with it, palms sprouting left and right out of the ground and marble mounds from the drilled out coconuts filling every nook and cranny. Every 10 meters or so, a halved coconut hung from strings. These were “Uga traps.” When night falls, the Ugas emerge in search of coconut and other snacks. The traps are easy pickings, and the Uga use one claw to hang onto the rock and the other to pick at the coconut trap. With one of their claws being used for support, these normally speedy land crabs are sacked by the adventurous hunters. Good, easy eating – as long as you keep all your fingers.

After counting all my fingers and toes to make sure I still had them, we reached the opening to the chasm. An endless set of tiny steps led down so far the darkness enveloped their destination. I was the last in line to make the descent, and watching Vlad, Mike and Hine descend into the massive crack gave me a little more perspective. They were engaged in some intense conversation about travel and barley acknowledged that they were walking into the earth. Add 10 surreal points. When I couldn't see them anymore, I heard an out-of-sight Vlad say, “Wow.” I couldn't have said it better. There were so many stairs, light just couldn't follow me down to the bottom.

The pool was similar to the first but much longer and narrower. We started to climb up the walls and jump into the barely visible water. Mike discovered that we were not alone in the cave. A huge milky-eyed eel was poking his head out of one of the cave walls and taking tabs on his new visitors. Hine wanted nothing to do with this and promptly got out of the water; however, all the boys rushed over to check out the eel. Sure enough, our huge eel friend, with a head the size of my thigh, was eyeing us. No worries, these eels are friendly and celebrated throughout the Pacific because they filter out contaminants in the water. Thanks, buddy.

Exiting the cavern was equally as impressive as entering, like re-emerging from a deep sleep. It was time to check out the east coast, the stormy cost, of Niue. It was only a short walk down to the water’s edge, but as we moved along the trail you could hear the pitter patter of coconut crabs scrambling around deep within the rocky forest. Daylight was starting to fade. The shoreline, which was normally quite a spectacle of waves and whitewash, was calm and opened up an endless waterfront of tide pools.

I sat and watched each wave attempt to crush me as its force dissolved into a friendly ripple that slapped against my ankles. Coral fingers extended out into the breakers, and being bold (or stupid), I sat down on one to feel the power of the ocean shake my new limestone throne. I might be at a loss when it comes to a plan, but watching the repetitive waves while being completely still gave me an unexpected serenity. I bluntly asked the ocean what I should do, “Where should I go now?” Half expecting a serious answer, the gargles and growls of the waves were my only response. Maybe in time the ocean will tell me. Or maybe I should just start being more decisive.

Our day last day in Niue was coming to a close, and back on Panache Vlad and I talked late into the night, knowing this would be the last time in a long time that we could have a conversation like this. Things were going to change. And gauging by our almost urgent need to chat, I guess things had already changed. We had always had time, but as the sun started to rise, we both knew time was no longer limitless.

The next morning was rushed like any travel day. Brian from the yacht club raced me and Vlad down to the wharf, and for the last time, we launched Buoy, my dinghy, into the sea. We hugged goodbye with Vlad firmly on land and me bobbing awkwardly in the water, and then he was gone. I was officially alone. Again.

I had been alone for eight months prior to Vlad’s arrival in Tahiti, but this feeling was different. I wanted to do a solo passage then, and now I want nothing more than company. I decided to wait until the next morning to shove off, and opted to watch Point Break. This was my last ditch effort to ignore the miles ahead of me. My passage to Vava’u was short, only two days, but Vlad’s absence was a real shock to my morale. Vlad was intelligent, competent and as entertaining as crew can get. To burn as much time as possible on the passage, I watched movie after movie. I was avoiding my trip. I was avoiding the present. I knew this was a sign that I couldn't possibly continue on this sailing trip and enjoy myself.

When I arrived in Vava’u, I was ready to give Panache to the first Tongan that looked at me and fly back to the United States. It just didn’t seem worth being alone again, no matter how amazing my surroundings were. Once attached to a mooring ball, and after several deep breaths, I regained my senses and started musing on ways to continue on.

I talked with Eliot, gave them the full rundown of my disaster on Niue, and described how radically my plans have been changed. Lots of Oooooohs and Aahhhhhs later, they described how their plans have also changed. They were no longer going down to New Zealand. Their rational was purely financial – it would cost more to do their boat work in New Zealand than in Fiji. So Fiji it was. They had zero problem with changing their original plan. I thought about this a moment and concluded it was foolish to be so caught up in my ego about not making the passage to New Zealand. Firstly, a prudent sailor is a good one, and if I wanted to cruise further south to explore Fiji, Vanuatu, the Solomon Islands and Papua New Guinea, it would ultimately be easier to leave Panache in perfect position to continue on instead of making a 2,200 nautical mile detour. I would love to cruise New Zealand, but I needed to take a break from cruising in general. I need creature comforts, I need convenience, and most importantly, I need to make a little more money to keep cruising. I need to miss cruising to regain my original drive.

If I stayed here in Vava’u, I would pay a minimal cost to dangle on a cyclone mooring, pay premium cost to get to New Zealand and pay zero cost while finding work and WWOOFing on a friend’s farm in the south island. I was starting to have a plan.

Eliot and another French boat opted to check out some of what Vava’u had to offer, which according to my cruising guides was quite a bit, before they departed for Fiji. I decided to stick around town, suture up my cyclone mooring situation and start my land vacation early. I ended up getting a great price for a private mooring and planned on flying to Auckland sometime in early December. Come May I would be back in Vava’u and ready to see everything my Tongan Cruising guide gushed about.

My first chapter of the Pacific was practically over. I was going to see New Zealand regardless of not sailing there. Richard from Latitude 38 emailed me about my aforementioned “failure” in getting Panache to the land of the Kiwi bird:

Listen dude, you didn't fail at all! What you've accomplished is incredible. Everybody has fuck-ups and setbacks. Give me a couple of days and I'll list mine. The important thing is you charged after your dream. You probably don't even realize that in the last year you got the best 'bang for the buck' real world education you could have possibly gotten. All the responsibility you had, all the decisions you had to make, all the squeezing of finances. I don't care if you stop tomorrow, you're a much smarter, wiser, self-sufficient person than when you left San Diego ... Keep the chin up, man, be proud as hell because you should be!Richard wasn’t the first to scoff at my declaration of failure, and he will not be the last. Knowing I am entering a break from sailing my body is calm and my mind is particularly clear. I am reclined in a comfortable patio chair in Tonga. I look behind me and have to squint because I am looking back 8,890 nautical miles to California, to where a version of me stands on the edge of exactly what I was looking for a little over a year ago – adventure. As I turn my head back around to take a sip of my New Zealand beer, everyone’s words of support start to make a lot more sense. I’m smiling because I got exactly what I wanted.

Glad to hear you’ve got a plan .. and a good one at that! Your life has been so full of adventure already, more than most have in a lifetime .. be proud and enjoy! Heck, we’ll be happy to finally leave the dock … LOL!