Sail Panache

Strutting across the PacificBlog

Leaving Ain’t Easy: An El Salvador Departure

While planning my Pacific crossing from a comfortable bar stool in El Salvador, I was continually flooded with an itchy anxiety that could only be satisfied by leaving. Or maybe my anxiety was due to the wobbly table I was working on. Either way, I needed to make a move. Taking that first step is never easy, and I had no shortage of worst case scenarios swirling in my head to keep me hugging the earth, but strangely enough my personal psychosis about the trip was not what made my departure difficult. In a strange way it was like the world wasn't letting me take that first step.

After the revolution many of the solders became guards for varies stores and communities. The show of arms in El Salvador is very prevalent, and I never saw any crime.

The first time I tried to leave El Salvador, it was alongside Bella Star. Hotel California was playing in the port captain’s office during check out, and right then it became my anthem: “You can check-out any time you like, but you can never leave!” The lyrics were true. Sure enough, the next morning the sand bar we had to cross was closed due to huge swell. It was either too dangerous or the bar pilot wanted a full weekend; either way, Bella Star and I weren't going anywhere. Part of me was relieved that I could enjoy one more delicious hamburger, but the other part of me was disappointed. It took a lot of mental fortitude to jazz myself up to leave, and that motivation was all for naught.

Two days later the bar was back to its normal self, and Bella Star and I had our second shot. Rushing to put everything in its proper spot before getting underway is always stressful. I perpetually have the feeling like I am leaving something behind, that something important isn’t on the boat. This is a ridiculous feeling because my whole life is on Panache, and it has been that way for the better part of a year now. But this time the feeling was legitimate – my camera was missing. I tore the boat apart for an hour with no success. I was sure I’d left it on Bella Star, but Nicole strip searched her boat and came up empty handed. This little loss was a huge monkey wrench in my plan. I can’t go to the South Pacific without an underwater camera! I continued searching as the departure time crept closer. One important thing about leaving this particular estuary is that you need to leave on slack high tide. Outside that window the smallest swell can be dangerous for boats entering or exiting the estuary. All my searching caused me to miss my departure. I waved goodbye to Bella Star in a distracted fury that was the epitome of unsatisfying. I felt bad for leaving our long-standing relationship on a sour note. But I couldn't help it. It felt like my trip was over.

I sulked around Bahia del Sol that evening having to explain to everyone in the El Salvador Rally why I was still at the dock. All it felt like was a bad excuse. I originally wanted to leave April 30 but was now 30 days late and apparently too chicken shit to make a jump I so brazenly declared a week prior. I felt like I broke a promise with everyone I told, but more importantly, I broke a promise with myself. Even Knee Deep, the last bit of family I had in El Salvador, was flying back to the States that evening. I remember when Knee Deep told me they were going to stay for another month before heading back to the States, and I thought to myself that that was totally bonkers! I mean, Bahia del Sol was nice, but come on... a cruiser can only drink so many dollar beers. My mind was attacking itself silently while I sat in the open bar with Knee Deep and Naomi from Medusa, a Columbia 23. I was stewing.

A group of lawyers enjoying a bachelor party on the estuary. Great guys and very generous with their scotch.

Naomi ended my self-deprecating spell once she realized I was starting to grow devil horns. “No worries. Tomorrow we can go into San Salvador, get you a new camera and then you can be on your way. No big deal.” Hmmmm, I guess it was that simple. It’s interesting how quickly you can snap out of a bad mood, all you need is the right buffer, and Naomi was it. Naomi, a quintessential surfer girl from New Zealand, sailed her trailerable boat from the northern tip of the Sea of Cortez all the way to El Salvador. She wanted to make it to Costa Rica but ran into the same bar crossing issue I did and then had trouble finding adequate crew. She was now stuck in El Salvador. She was probably as frustrated as I was but obviously handling it much better. These setbacks are just part of the lifestyle, and they ultimately open other doors. Naomi was now essentially alone in El Salvador, roughly my age, and had a similar sense of humor. We made good company for each other.

If you are looking for a quick escape from Bahia del Sol, your dinghy is all you need. La Herradura is a quick 6 miles away.

With a new camera and an unplanned purchase of 12 coconuts, I was once again ready to depart El Salvador. Wearing a smile, I said goodbye to the remaining rally participants soaking in the pool and slowly pulled Panache away from the dock. A little too slowly. I let the motor warm up for a bit then gave her full throttle. I couldn't breach 2 knots. Something was wrong. A quick glance behind Panache revealed black sludge burping into the estuary. For whatever reason, the engine was working overtime. Whether it was barnacles up the ying-yang or a rope wrapped around the prop, I was once again going nowhere. I immediately throttled back and stood clenching my jaw. Turning 180 degrees stung my pride. The camera and sea state were out of my control, but this failure was my fault. I should have cleaned the bottom before I left. Zack 0, El Salvador 3. The scoreboard was looking grim.

Do you see a trend yet? Yeah, everyone eats lots of pupusas in El Salvador. Its just as big of a food staple as tacos in Mexico.

I hastily dropped the anchor and immediately dove into the dirty estuary with the little remaining sunlight still illuminating the brackish water. My prop had a basketball-sized clump of weeds choking it from spinning freely. Barnacles also accompanied this rat’s nest. No wonder I couldn't go more than 2 knots. The good news was that this was a simple fix, no terrible mechanical issues, but the bad news was that I was still in El Salvador. This particular estuary stretches for miles and miles through snaking mangroves and villages. The current is incredibly strong and sometimes carries entire palm trees with it. I fell victim to some huge clump of Dyneema-strength weeds. I explained my new excuse to everyone. At this point my leaving El Salvador was like a running joke. I refrained from telling people when I was leaving because I didn’t want to lie, I honestly didn’t know when El Salvador would let me leave. The bar pilot told me in two days we could try again, try being the operative word.

Meanwhile, all the fresh provisions were starting to go bad. A carton of 20 eggs turned out to be a breeding ground for thousands of maggots; a wonderful smell and an even more wonderful cleanup. My cabbages were molding faster than I could eat them, and most other fresh things were starting to become anything but. What a waste. I was able to salvage most items, but I ended up throwing a bunch of it out. I hate wasting food and try my hardest to eat everything before it goes bad. I guess that’s why people call me “the goat.” Simultaneously I was doing my best to not eat it all because these were my fresh provisions for the crossing. It was a conflicting problem for a goat.

Getting exceptionally drunk with Naomi out of circumstantial frustration proved to be extremely fun. We bartered with the bartender for a bottle of rum, soda, and a bag of ice. We played cards under lamp light late into the night and did our best to ignore the huge thunder storm crashing right outside Panache. We both woke up with raging hangovers and a big project on our plate; get Naomi’s boat on the hard. A couple days prior we de-stepped her mast in preparation for today. Naomi was heading to California for a wedding and was leaving her boat in a local’s yard to weather out the rainy season. Even with my slowed state I was able to help. We plopped Medusa on a pile of tires and called it good. Breakfast was fortifying but hard to swallow. After a long nap it was time to get my prop back to working order. I didn't feel good about swimming in the water, but I didn't have a choice. It was really dirty. The kind of dirty you can smell. I was convinced I would contract some sort of STD from simply touching the water. I would've worn protection, but I had none. The prop had an inch-thick coating of barnacles that made it easy to snag passing debris – no wonder I had such a rat’s nest attached to it! With no other serious projects on the boat, I headed into Bahia del Sol for some internets.

I was ignoring Facebook and my email because I didn't want to have to explain why I hadn't left El Salvador. It was just too long of a story for a simple Facebook update, and to avoid questions I could only peek. No posting anything. No “liking” anything. And no signing into the chat function. It was a one-way media blackout. When I logged into my email I was pleased to find numerous messages from Bella Star, who by that point had made it to Costa Rica and were enjoying a postcard-perfect anchorage all to themselves, right across the Nicaraguan border. Oh, and some bad/good news...

Hey there. Nicole here. So guess what? If you can believe it, we found your camera last night... Yep, that's right. You want to know where? Under the settee (where you always lounge) nestled amongst the canned goods. Seriously! I've got the seat propped up, and I'm digging around for something for dinner when Aaron says, calmly, "There's Zack's camera." I'm like, yeah right. But there it was, sitting on top of a can of enchilada sauce, leaning up against a container of mayo. WTF!!

On a can of enchilada sauce! I KNEW IT! It was all part of a fucked up plan to get me to come south. I thought the Canadians were sneaky, but this was some real 007 shit Bella Star pulled. No worries. I now had a new camera, so did I really want to go way out of my way to pick it up? I wrestled with this for a long time but was undecided. It would be nice to have a backup point-and-shoot camera, but was it worth getting sidetracked for possibly weeks? I didn't even know anything about Costa Rica. I dropped the waypoints in my chartplotter and decided I would see how I felt once I got back on the water. The reality is that any plan CAN change, but cruising plans certainly WILL change. Someone once told me that cruising plans are written in the sand at low tide. They are easily washed away. I guess it’s a great lesson in being flexible.

When its raining at night the best thing to do is go swimming. Here is Mickey taking a jump into space?

I settled in that night getting the last bit of Panache ready for her fourth planned departure. Dinner was some tuna casserole I found stuffed in the corner of my fridge. It was old, but it passed the smell test. Anyway, I am a goat and can’t throw anything away. It needed to be eaten. I burned the hell out of it and added a gallon of hot sauce and called it good. It was a simple meal that my stomach accepted. Two hours later I paid the ultimate price. The only good thing about food poisoning is that when you are sitting on the toilet chugging a bottle of Pepto-Bismol you know this discomfort will eventually end. Fourteen hours later it did, but I missed the slack tide once more and looked like a complete ass. This fail was absolutely my fault. I don't think I will be able to eat tuna anything for a long time. Just writing the words “tuna casserole” produces a gag reflex. That night I ate a packaged meal of top ramen and two liters of Gatorade. It wasn't nutritious, but it also wasn't cram packed with vomit-inducing bacteria. Everyone was happy.

The next day was vomit free and it seemed like everything was finally in place. The bar crossing took a long time but was a non-issue. I had no breaking waves to overcome and my prop was propelling me at a constant 4.5 knots. I thanked Bill and the bar pilot and gave some final goodbyes to everyone over the VHF. El Salvador was fading into the distance as a solid 10 knots blew across my port beam. It felt amazing to be back on the water. I had finally escaped the gravity of El Salvador; it only took 5 tries. It was decision time: Do I head to Costa Rica or high tail it to the Marquesas? I was provisioned for either trip. The plan I had so deliberately outlined in the sand over the last month was gone with high tide, and it looked like Costa Rica was the appropriate next stop. I changed course by 60 degrees and started beating into the wind towards Bahia Santa Elena. Crossing the Pacific wasn't excluded from my new plan, in fact, heading to Costa Rica just put me that much closer to the Equator, that much closer to the trade winds. Being in Costa Rica also put me in a prime position to visit Isla del Coco, a small island said to have some of the best diving in the world. The more I read about Costa Rica the more comfortable I was with my decision. Well, as comfortable as you can be while beating into the wind.

This little guy (a baby Great-Tailed Grackle) fell out of his nest. I cared for him until he decided to wrap his devil claws around my arm.

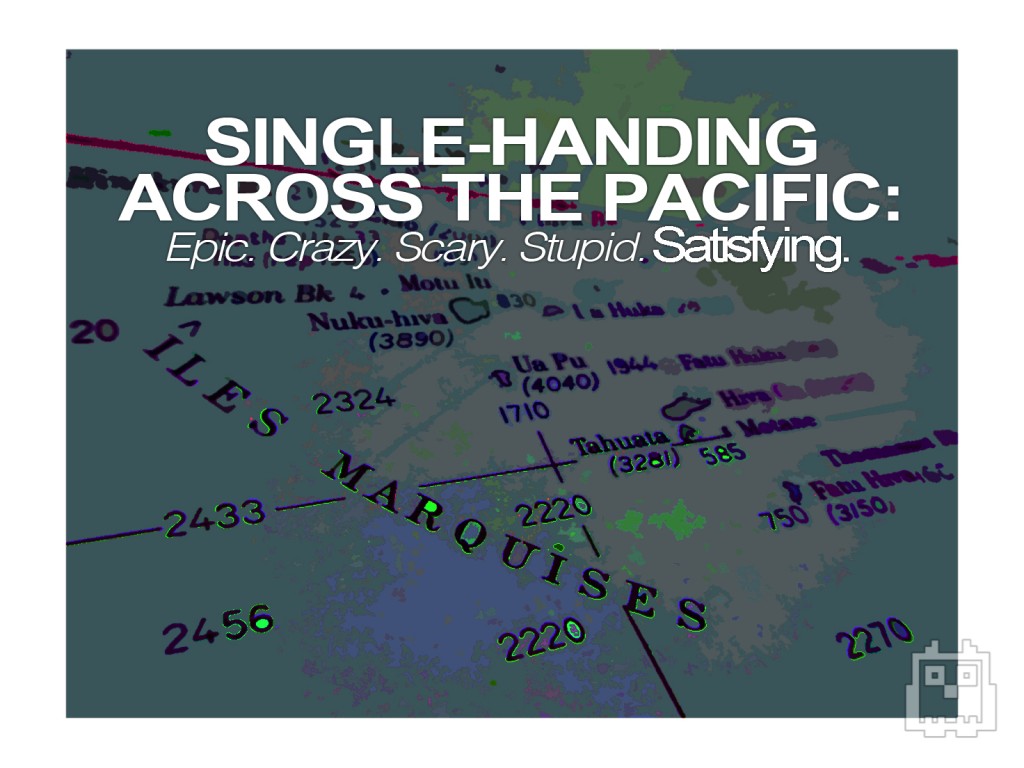

Single-Handing Across the Pacific: Crazy. Epic. Scary. Stupid. Satisfying.

For as long as I could think about sailing, the idea of cruising across the Pacific Ocean has been a lingering thought in my subconscious. There are few places as isolated and that hold such a strong magnetism as the Pacific Islands for sailors. This thread of thought has spooled itself from a vague pipe dream into a legitimate opportunity. I have just enough money to cross the Pacific, the necessary paperwork to clear immigration, the proper boat and knowledge to sail her, and I am conveniently placed at the tail end of the season to cross. I can't ignore the freedom I have to go, and I feel 100% obligated to take advantage of my circumstance. I feel so utterly lucky to have such a brilliant opportunity in front of me and know I might never get this opportunity again. My emotions roller coaster from being extremely excited to totally terrified. I have been brushing up on the heavy-weather tactics I might have to perform, and they make the bad weather I have experienced so far look like child's play. I push those thoughts aside quickly. Heavy weather sailing accounts for a very small percentage of cruising time. It just makes sense to continue the positive cruising momentum I have created for myself and tackle the next level of sailing. An open ocean passage.

Panache has made this trip before back in 1979 and cruised all the way to Australia. She has seen many places and met many people. The fanfare that follows Panache is incredible. On numerous occasions I have been contacted by people who are delighted to see her back on the water. When I bought the boat from Tony Barra, the one and only previous owner, I spent hours talking to him and hearing his stories aboard Panache. Almost all of those stories took place in the South Pacific.

I remember taking time off work to train down to Ventura, California to look at Panache. I seemed to catch Tony by surprise. He gladly offered to show me the boat, but I could tell he was apprehensive. He had been passively trying to sell her for seven years, but I believe he was just looking for the right person to sell her to. I had dozens of questions for Tony, but in the beginning he was firing more questions at me. Almost like a pre-approval for purchase. I must have answered correctly, because he provided honest answers to my questions and started actively selling the boat. What works? What doesn't? What would you add? And so on... After a simple day sail, the stories of the South Pacific followed. I listened with a big smile, my mouth half open. I wasn't listening to his stories, I was there. Nearing the conclusion of my visit, he looked around Panache with a smile, appearing on the verge of tears and told me the boat would take good care of me, that he wished he could go cruising again in the South Pacific.

I can’t fully explain my drive to sail into the middle of the Pacific. It’s a mix of things; a rite of passage, an unequivocal experience that needs no explanation, a true adventure. I guess that’s the biggest reason. Adventure. I will be leaving a continent for fuck sake. Tony knew I wanted to head to the South Pacific but was thrilled to sell Panache to someone who would give her a second life, regardless of where I took her. When I broke the news to Tony that I was going to cross, he was very excited for me. It was what Panache was meant to do. It’s like I am taking Panache home again. Despite my desire to go, the one true prerequisite in heading to the South Pacific is having enough money. Sad but true. Tony made this plainly apparent.

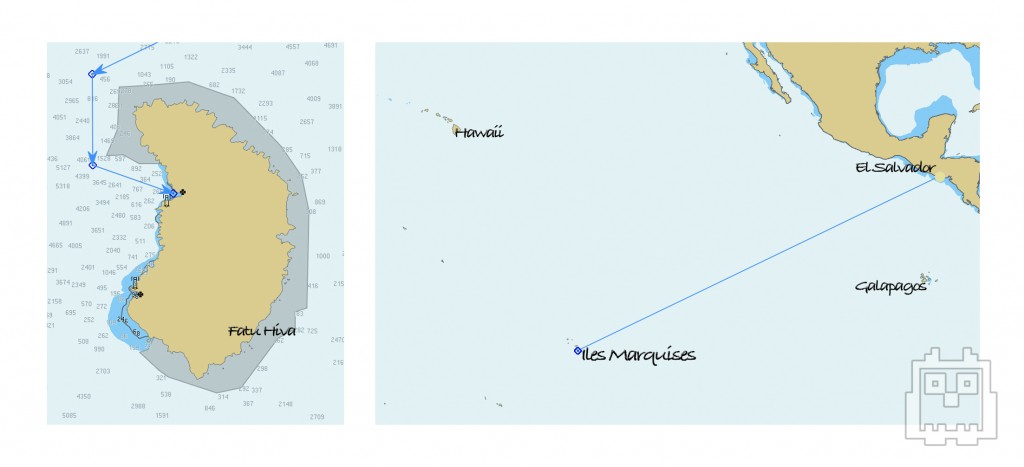

This image should give you an idea of the scope of this passage. This route is as the crow flies, not the actually route I will be sailing. This image is a screenshot from OpenCPN, the free navigation software I will be using during the crossing.

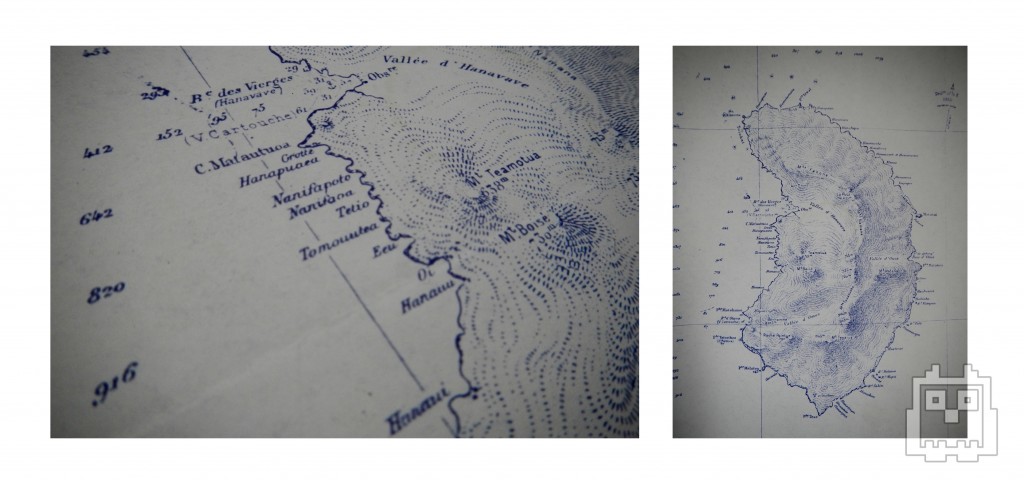

Old French chart of Fatu Hiva, the southern most island in the Marquesas. This will be my first landfall.

I hate talking about money, but it's impossible to ignore such a crucial part of travel. Mexico and El Salvador have been extremely inexpensive and make the task of following a budget essentially a waste of time. Traveling to the South Pacific on a budget is generally considered contradictory because it’s so expensive. NO BUDGET IS BIG ENOUGH! Just kidding, but it’s still crazy expensive. Not only is provisioning expensive, but preparing for the trip, having a capable boat and getting the proper paperwork are also costly. French Polynesia requires sailors to post a bond equal to the reparation cost for returning to your home country. In my case, that bond is 2000ish dollars. French Polynesia doesn't want to get stuck with a bunch of bearded, smelly internet-hungry sailors. I would be curious to see the average mile per dollar cost for a passage to the South Pacific. I’m sure it would drop my jaw.

Once in the South Pacific the financial rape doesn't stop. Being so remote, nearly everything is imported, and imported stuff bears crazy high prices. For this reason, my provisioning includes food not only for the crossing but through the island chains. This should help alleviate expenses, but my meals will be anything but spectacular. I have enough rice and beans to fart all the way to Australia and the vitamins to make it nutritious. Essentially, I will be a walking carbohydrate by the time I land in New Zealand/Australia/Hawaii. I have yet to decide the endgame of this passage, but I have committed to the first step. The hardest step.

This is one list/receipt combo of three. Provisioning in El Salvador was a huge production and took three days. The only thing I couldn't find was a Tarp. Whatever.

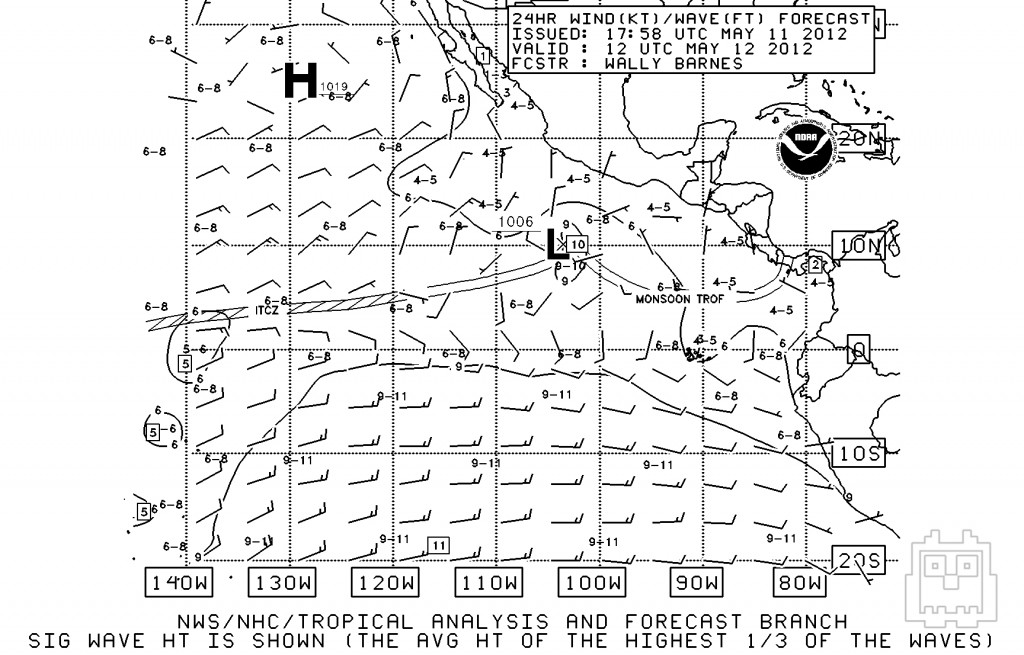

It’s a little hard to look so far out in my journey when the biggest step of all is only days away. All my preparation has blinded my ability to plan beyond the first month or so. Sure, I have worked out contingency plans through the South Pacific, but I have no idea which one I will execute. It’s kind of like a real life Choose Your Own Adventure; turn to page 38 if you want to head to Fiji, or turn to page 68 if you want to stay in Samoa for another week. Either way, I will have plenty of time to figure that out during the crossing to the Marquesas, a trip that spans over 3300 nautical miles (as the crow flies) and will likely take 35 days, assuming my average speed is 4 knots. The wind should be consistent, but the Intertropical Convergence Zone (also known as the ITCZ or the doldrums) could balloon my expected arrival well past the 35-day mark. This is ok. Time is only dangerous if you have no way to spend it. That being said, I am immensely afraid of myself. My thoughts. Sailing solo down the Mexican coast provided trying times mentally. The isolation produced a prying introspection that forced me to wrestle with myself – and these previous passages were only three days long. To combat idle hands, I have created a daily schedule for my body and mind to be active. A routine. I even bought a Kindle, a device that has made reading cool again.

Essentially, I am creating a groove to follow during the crossing. It usually takes me two days to fall into that groove. Without the groove, the simple rocking motion of the boat can be arduous, even painful. However, on that third day, that magical third day, my body acclimates. I have prepared several workouts to nurse my body. Reading my Kindle, keeping meticulous logs and journals and baking fresh bread in my new pressure cooker will nurse my mind. I have provided enough activity, mental and physical, to make the passage less daunting. That is the Pacific crossing in a nutshell; a mental endurance race.

The first of many bread loafs baked in my pressure cooker. I will be eating fresh bread all the way to through South Pacific!

As I write this, I am on a bus back to the Bahia del Sol marina to finish preparing Panache. It's already May, and the season is closing for crossing the Pacific. I originally wanted to leave April 30th, but like most places I have spent extended periods of time, El Salvador has provided many good memories and a creeping feeling that I want to stay. I think every cruiser fights with this yearning for home. It’s a yearning for the familiar. My finances create an urgency to keep moving. Many other boats don't have this urgency because they have the money to wait for next season. I have neither time nor money to wait. If I want to jump, I have to do it NOW. I sometimes feel rushed, but looking back at my preparation, my checklist, I am ready to leave. I guess I am just sad to say goodbye to the people I have become close to. Bella Star, Knee Deep, these boats are my family. They have become the familiar, and now I have to say goodbye. It’s hard.

The last meal in El Salvador with my cruising family. I will miss you guys! Images © Bella Star 2012

It seems like everyone is lobbying for me to go south to Costa Rica and Panama. I am not interested. I would love to travel there, but deep down I know these countries are easily accessible. Nick from Saltbreaker put it best when weighing the options, “You should probably cross. Central America is great and all, but it's easy to get [there] by plane and still see just about everything. Try backpacking around the Tuamotus... not gonna happen.” It’s a huge commitment with lots of glory. It’s one of the biggest crowning achievements a sailor can conquer. Nick was right; Central and South America are extremely accessible. Why use all my current limited resources to go somewhere I can go at any point in my life? The sheer distance I will have to travel makes a Pacific crossing that much more appealing, and it ultimately made my decision to cross that much easier.

Being a single-hander adds a little more complexity to such a long trip, but it also adds a considerable amount of glory. My mother is taking my plans quite well. I have a life raft, I have an EPIRB (emergency position-indicating radio beacon), I have a suitable lifejacket and harness, enough food and water, and the will and perseverance to get there. I have explained this to her, and she mustered all the support a worried mother can:

I don’t know what is driving you on this adventure, but I know you will be fine...I feel it. It probably will not be easy however. Keep the dingy and that beacon ready in case you need it. The storms are what worries me. The 6+ foot swells... Remember that the Pacific Ocean is the color of Krishna, one of the visible manifestations of God in Hindu religion... so you will be in his arms. Sorry, I'm so sappy.Love you mom. Life raft and EPIRB aside, if I fall off Panache, I will literally need a miracle to save my life – this is my BIGGEST fear. 90% of the time Panache is being sailed with self-steering, and if I fall off, I will have the terror of watching her sail off into the distance while I float in the water indefinitely. I have jacklines and a harness to strap into, but I’m sure some extenuating circumstance exists that can rip me off Panache and into the never-ending sea. I hope I don't find it, but the thought gives me chills. It literally haunts me. While preparing Panache I had the realization that my life ring and man overboard pole were worthless. If I fall in, there will be nobody there to throw them to me. I will be the definition of alone while in route to the Marquesas.

With a free program called MultiMode, I am able to download these weather updates through my SSB radio. It's extremely macro, but will give me a jump on foul weather.

Not to get all dark and stormy, but these thoughts can’t be ignored. They should never be ignored. Plan for the worst, and you probably will never see it. I talked to Tony Barra recently to grill him with all my anxieties about crossing. He was happy to hear from me and answered all my questions. “Let me give you some advice,” Tony started, “An old sailor’s tradition, never leave on a Friday. It’s bad luck. In the old days boats would wait at a river’s mouth until Saturday morning and then leave. I don't know if its true or not, but every time I left on a Friday, the trip sucked!” We laughed about this, and I promised to not leave on a Friday. I realized that all my anxiety was a waste of energy, that Tony qualified me ready because out of all my questions, the biggest piece of advice he could give me was to adhere to maritime superstitions. Thanks to everyone who helped me prepare for this trip, and look out for my arrival post 35ish days from now.

ZSOL