Underway again and still looking back not forward. People say never look back, but in this moment the view was better back there. The green-capped mountains of the Marquesas were blurred by the increasing level of atmosphere separating us, and as I followed the slight but noticeable curve of the earth, their landmass slid ever deeper into the seemingly endless bath we both sat in. Turning forward with a sigh, I could see no sign of Rancho, any other vessel or anything. All that lay before me was the inescapable horizon – two blue ribbons, the sky and the ocean, resting on each other. Rancho left Baie Hanamoenoa a day earlier, eager to check out a perspective haul-out facility in Apataki. And while we had no line of sight, we remained connected through a lower frequency on the electromagnetic spectrum. Thanks to my HF radio, we exchanged “hellos” and weather info every evening. Traveling at my current speed of six knots, my passage to the Tuamotus would take five days plus another five to Tahiti. I could use the break in the Tuamotus, but I was still undecided whether the so-called dangerous archipelago was worth the visit.

For underpowered or under-crewed vessels, the Tuamotus can be a dicey stop. Panache fit both categories, so the decision should have been easy. But I have read enough about the Tuamotus to know that they are one of the most magical places in the South Pacific, if not the most beautiful. Sailing past the Tuamotus would make for a 10-day passage to Tahiti. Not impossibly long, but long enough to make me think twice about risking a layover. So what’s the big fuss about stopping?

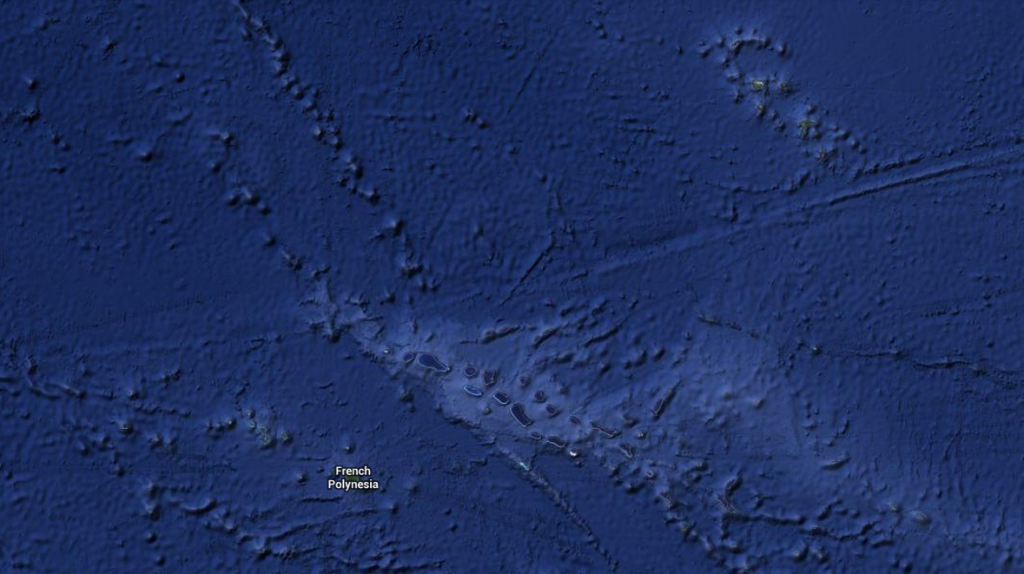

Well, the Tuamotus are a group of atolls, or ring-shaped reefs, with lagoons in the center. Almost all atolls have one pass boats can enter to enjoy the protected, postcard-perfect blue lagoons. The problem is that entry and exit times have to be choreographed with the fluctuating tides. Not too difficult, but if you enter at the wrong time, you could be battling 7 knots of current that desperately wants to smash your boat against the jagged coral teeth lining the pass. My 12HP engine wasn’t up for the battle, and my nerves weren’t either. Once through the passage, the excitement isn’t over. Inside each lagoon waits massive sea-mines posing as coral heads. I can’t man the tiller and keep a bow watch at the same time. Or can I? All this atoll business sounds pretty sketchy, but there are numerous atolls that are very well charted and pose little threat to the timely, well-read sailor.

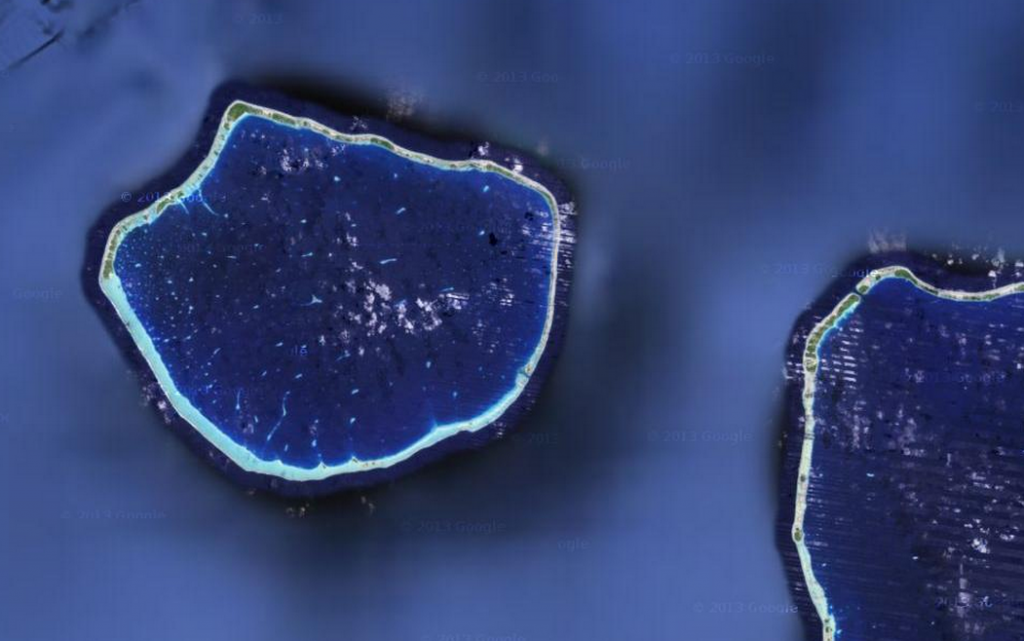

The big picture! The Marquesas in the top right hand side, the Tuamotus in the center, and the Society Islands in the bottom left.

I did the reading, can time an arrival and can clench my teeth, but the jury was out as to whether I would stop or not. I eventually decided to read through my Tuamotu guides once more (I certainly had the time) and gun straight for the main passage cruisers use to thread through the archipelago. The gap lies between Rangiroa (the largest atoll) and Arutua and spans 18 miles. This option put me in prime position to stop at a number of atolls if I needed the break.

The first day out was void of excitement, always a good omen that allows me to ease into a passage. The wind was pile-driving Panache through cloud after cloud of spooked flying fish. I stayed on the bow for hours, reading my Kindle and saving the unfortunate flying fish that flew a little too high and found themselves on the hot fiberglass deck. With every saved fish, I was gaining important karma for the hundreds of miles ahead of me.

All my fish saving must have barely offset my fish murdering in the Marquesas, because the weather turned quickly as night approached. Weather turning quickly? This was a familiar but fogged memory from the doldrums I would rather forget. Muscle memory was better than actual memory, and I had the first reef in the main before I could regurgitate any fear. I downed the 90% jib (my working jib) and set the storm sail to keep calm and carry on. I could probably have had more sail area up, but I was in no big hurry, and to get a little sleep I needed to reduce more sail area than was necessary. My co-pilot Jesus (the self-steering vane) was doing all the hard labor and making me look quite lazy. The weather for the first couple of days was very fresh, and when I established radio contact with Rancho, they informed me that it was going to be another four days of increasing weather, peaking sometime on day three. Four days of building, rough weather equates to numerous sail changes daily, little sleep and disruptive rain showers that leave my body perpetually damp.

You might assume my biggest annoyance would be physical discomfort, but that’s only second in line to my food situation – specifically my cooking situation. Sometime during my first stop in the Marquesas, my El Salvadorian propane exhausted itself, and by default I was on a raw food diet. Rancho Relaxo was nice enough to invite me over for several hot meals. It should be simple to refill a bottle of propane, but for some perverse reason, the world has decided to disagree completely on a universal propane regulator. World peace might be a little ambitious, but a universal propane fitting!? Totally doable. In the wake of my failure, Rancho invited me over for several more meals. Nobody in the Marquesas would even sell me a new tank. Too much of a scarce commodity, I guess. Without being able to get my hungry hands on more propane, I begrudgingly promoted a little camp stove to replace my dedicated two-burner gimbaled rig. This was a shit way to cook anything. It’s hard enough to make a decent meal underway with a gimbaled stove, but when one hand is busy keeping your cooking apparatus/pot/pan/whatever stationary, your meal options are reduced to just-add-water snacks. After many days where breakfast, lunch and dinner featured pre-packaged, sodium-packed soups as the centerpiece, I got a little bored. I dreamed of salad. I can only imagine what my 5-year-old self would think of this.

One night I ambitiously attempted pancakes. Preparing pancakes in the best cooking situations can be hazardous – at least the way I make them. I prefer to fill a skillet with a shallow pool of oil and sink thick batter dollops into the volcanic liquid. Without the stove moving I have a 20% chance of suffering some kind of cooking-related injury. With my gimbaled stove the probability shoots up to 50%, and with my non-gimbaled death stove (my current cooking situation), I assumed injury with every meal.

One quick check outside to see if Jesus was not sleeping on the job and that the weather was going to be consistent for the next 30ish minutes, and I was stuffed back below to mix my hotcakes. Back in El Salvador, I made my largest provisioning run at some Costco-style bulk store. My genius picked up a whopping bag of Northwest style, just-add-water pancake mix. Powdered Americana deliciousness. Super filling and easy to make. As I opened the unwieldy bag, I kept repeating, “Super easy to make. It’s super easy to make, Zack. Don’t spill boiling oil on your man bits, Zack. Pancakes, super easy to make.”

Oh, and I was naked. Nakedness on a boat is pretty standard issue. It’s hot and sticky, and clothes are not always a good option. In the current weather conditions - rain, rain and more rain - I prefer to do sail changes naked because I can keep my clothes dry while simultaneously taking a ghetto shower. Cooking with hot oil while naked should have been a red flag, but I blame it on the fatigue.

Anyway, my muscles ached after ten tedious minutes of flipping pancakes and bracing myself in Panache’s modest galley, but I had my hotcakes. I sustained minimal burns, thankfully none of which were on my man bits. The pancakes ... well, they looked like they were stuffed into someone’s pockets during an Iron Man and then slopped onto a plate post finish line. Woof. No points for presentation, but they did taste delicious. I ate with my eyes closed. That night I reduced sail area again and slept for an uninterrupted hour, being graced only with short cat naps after that. I was groggy the next morning, and the sea state just kept getting worse and worse. Sheets of rain would disrupt the otherwise sunny day, and the washing-machine swells urged me to stop and take a break at the Tuamotus.

It was time for a radio check with Rancho Relaxo. They had a Pactor modem and could receive weather fax, which is invaluable information for someone considering a stop in the Tuamotus. I caught Rancho as they were approaching Apataki. They gave me some grim weather information: predicted winds were to build and crescendo in two days’ time before dying down to a lazy 15-20 knots from the east northeast. We had enough time to exchange lat/long positions, but our communication was cut short because their entrance was starting to get too sketchy for David to casually chat down below.

I paused for a moment, carefully listening to the hiss of white noise. Hmmmm, busy avoiding shipwreck, eh? If Rancho was having trouble entering atolls with its big Volvo diesel and extra crew, how the F would I fair? I made the call. Play it safe and skip the Tuamotus. With pursed lips I got out my computer and revisited my “No Tuamotu” contingency plan. From my current position, it would be a day before I would get my first (and possibly last) sight of the Tuamotus. The next day I would thread the gap between Rangiroa and Arutua, and then I would say goodbye to the archipelago and start the five-day, obstruction- and atoll-free sail to Tahiti.

As I crept closer and closer to Manihi, my frequency of scanning the horizon accelerated. Ten miles out and nothing … 9, 8, 7 miles out and still nothing. How screwed up are these charts!? I would normally tack and not get so close to such a dangerous shore, but I wanted to make sure I could have enough space to make the gap. I needed to stay as high on the wind as possible. With a breaking sigh of relief, I finally spotted Manihi 6 MILES OUT! No wonder people run into these islands! I was lucky enough to be making this portion of the passage during daylight. The sea state didn’t make it easier to see anything, but when lifted by the crest of each wave, I could see a gold line representing a beach and a jagged green line of palm trees. This game of peekaboo lasted the entire length of Manihi, and the perfect lagoon on the other side of the battered shoreline taunted my fatigued body.

Level ground was hard to come by on this passage. However, the crest of each swell did give me a good vantage to atolls I would never visit.

What could I possibly be missing? I convinced myself nothing, until I spoke with Rancho that evening. They had a nail biting entrance they described as a “close call,” and then a brisk sail inside the lagoon to the anchorage. After dodging bommie coral heads left and right, they dropped the hook and were finally able to absorb their surroundings. Rancho’s description included words like “beautiful” “amazing” and “incredible.” They spoke of the unique color of blue they have never seen before and the crazy volume of fish that filled every cranny of the lagoon. Well, shit. I shouldn't have asked, but at least someone was enjoying a break.

The strong weather met me at the gap, and I was making good use of my inner forestay and storm sail. At this point, I was beyond any point of return back to the Tuamotus, and the only thing I could cook efficiently was hot water for oatmeal and pasta. Re re repetition was the name of the game.

I wouldn't call the sailing difficult, just very needy. Little squall cells were constantly rolling over Panache, bringing rain, a reefing job and wet clothes. My harness is usually on, but night sailing in the choppy weather and gales demanded it. Every so often, the angle of swell and my current tack collided, sending a wave breaking into the cockpit. I don’t typically batten down the companionway hatch because it becomes too difficult to enter and exit Panache. The solution is a snap down cover to prevent floods of saltwater from entering my dry nest. Easy to snap down, flexible to poke your head out and waterproof to keep those swells outside. The thousands of miles I had sailed were finally undoing the cloth, and each cross swell made my world that much wetter.

I was effectively riding the squall line of the low pressure system. Sometimes I would be in front of it, but most times I was either right on it or deep within the dark mess. When the wind was above 30 knots, I would run a bit more with the wind to make for a smoother passage, but I needed to make southern progress to meet Tahiti. Lulls below 30 knots were my opportunity to make southern progress, but these moments were getting fewer and fewer the more I lost the race against the squall line.

Eventually the black mass outdistanced me, and I was in too deep. I needed to wait to make my southern progress. I dropped all sail area, and was magically sailing bare polled. In a moment of awe, I looked at Jesus, who was sailing famously, looked at the chart plotter that read a current speed of 6 knots (also my hull speed) and shrugged, convinced this was my break. It was the late afternoon, but it was so dark it might as well have been midnight.

It got much darker than this. This is what it looks like when the sky and sea tries to swallow you up.

I did the sail change dance for an additional day before the weather started to normalize, and a blue sky presented itself. Makatea, a little island nub splitting the difference between the Tuamotus and Tahiti, glimmered in the distance, and I finally knew my passage was nearly over. I started to see other boats in the far distance and hear French chatter over the VHF.

By the time I had a shimmering Tahiti in my view, I had consumed enough sodium for the remaining part of the year. I was ready to have real food, Inter-webs and a fresh baguette … and to flirt with the French. The wind all but died on my approach, and I ended up motoring most of the way. A pilot dolphin kept me company for an hour or two, but decided I was too slow and spun off towards neighboring Moorea. I was having a bit of trouble identifying the main passage to Papeete in the dark. Between the seizure-inducing lights from the airport, the blanket of flickering lights from the capital of French Polynesia and the numerous other passages into the lagoon surrounding Tahiti, my approach was at a snail’s pace. When I got close enough, I called port authority to request entrance. In English.

Once permission was granted, I continued to snail along. This is of course when I got a fuel restriction and bobbed uncontrollably outside of the entrance for 30 minutes before port authority called me back to make sure I was alright. I explained to him the vintage and status of my engine, and he gave me a forced laugh before I fired the engine up and continued on. Following a perfect line of lights, literally and on a chart plotter, I slowly edged my way into Papeete, a milestone conquered. I could smell the city. Hear it breathing. The acceleration and beep of cars and the thick smell of flowers laced with smog. It was an industrial port overflowing with palm trees and honeymooners. Working my way to the stern tie moorings in front of Papeete, I got a good sense for how small Panache really is. Panache might lack speed and comfort of some of the boats surrounding me, but we all ended up in the same place at the end of the day. My distant neighbor across the bay was a mega yacht that I saw leaving Costa Rica when I was there. I can’t imagine how much fuel they used to cover the same distance I did.

Backing into a stern tie dock was a major pain. It was a first and amounted to a 40-point turn that almost crushed Jesus off the back off Panache. After a very lively passage this was probably the hardest part. I hadn’t been tied to a dock in over 4,000 nautical miles. It felt really good.

I could have slept for three days straight, but I logged onto my computer almost immediately to announce my arrival, and I found this message on Facebook:

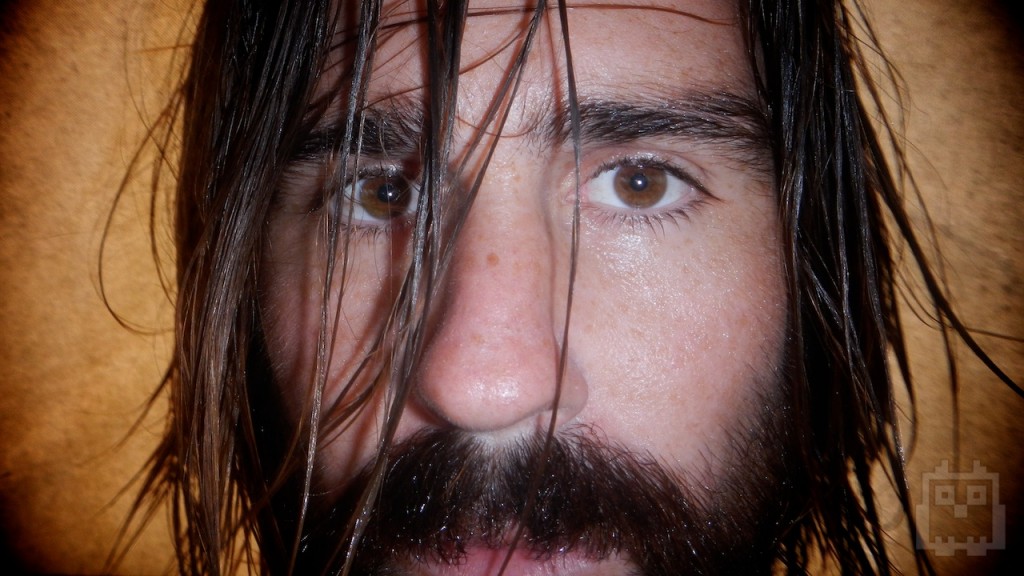

Hi Zach, Molly told me to reach out to you. I heard that you have been sailing around the world and recently made a call out for mates. I'm in a rather strange point in my life, I was supposed to get married in two weeks, then leave with her to sail/travel around the world for a year. I found out last week that she had been sleeping with another, older, man for the last two months so I ended things with her. I'm not falling apart mentally or anything, but I do feel an urgent need for something new. I am not exactly an accomplished sailor quite yet. I've taken an intro level class but thats it. I do learn very, very quickly and I am sure that I would be up and running within a day or two. I am not a novice, however, to travel and adventure. I've been to over 40 countries all over the world, and without tooting my own horn too much, I'm fucking good at having a good time. Anyways, let me know if and where you would like to meet up, or what your plans are in general. Thanks, Vladimir

I stared at the message, and then read it again. I felt bad for the guy, and while my “recent” breakup seemed trivial to his, I could still relate. What did I know about him? I went to high school with Vladimir but didn’t really know anything about him. We had numerous mutual friends, but never seemed to cross paths directly. I mainly remember him being a very small high schooler who toted around a backpack equal to him in size. I chuckled at this thought. It didn’t bother me that I didn’t know him. I liked how forward he was, how he was ready to trust me and commit to a serious sailing trip remotely. Furthermore, our huge stack of mutual friends made a strong case for our potential friendship. Halfway through deliberating, I realized I was desperate for crew, and Vladimir’s proposition was ideal. I had been solo for too long, and it was time for company. Going weeks without talking was mentally taxing, and the long-term effects to solitary confinement, no matter your surroundings, couldn't be healthy.

I would call him tomorrow.

The next message was from my mom begging me to find crew. How ironic. It’s so satisfying when things just work out. By the time I closed my MacBook and lied down, the sun was already coming up. I couldn't be bothered to see how different my surroundings looked in daylight and sank further into my bed, still damp from the passage. As alien as the sound of the city was, I had no problem falling asleep. After all, I had already sailed into a dream.

Panache next to the big boys. The other boats might be larger, but we all ended up in the same place.